Mortality and agency

Life has no meaning the moment you lose the illusion of being eternal.

Jean-Paul Sartre

As I was thinking about today’s post, I stumbled upon this supposed quote from Jean-Paul Sartre (1), which both completely captures the spirit of what I want to talk about but also threw me back instantly to the heady days of undergraduate life in the academic cloisters of the University of Toronto, Canada’s pre-eminent academic institution, and the place where I earned my first degree. In earlier posts I’ve alluded to the fact that, like most 20-something students, I was stumbling through life with no real clue of the mountains and valleys that lay ahead of me.

When I think of Sartre now, I remember myself as an insufferable young twerp who wore black as often as possible, held cigarettes (2) between thumb and index finger over a cupped hand as I imagined French philosophers might do, and carried a tattered copy of Being and Nothingness around with me on the subway, more for show than for anything else and even in the weirdly misguided belief that this accessory might make me more attractive to women (3). To anyone who would listen, I maundered on about the relief of mortality, the absurdity of living, the evils of capitalism, and the superficiality of regular life. Then, on weekends, I’d go home to mum and dad and enjoy a jolly good British dinner while my dear mother washed, dried, and folded my laundry. It’s funny to think about that now from the perspective of (optimistically) late middle-age or (realistically) the youth of old-age. If you live long enough, it’s inevitable that you will face moments of existential threat where, by reason of disease, war, misfortune, or oncoming Ford F450, you find yourself face to face with the prospect of your own death. I’ve recently come through one such threat myself (4). Full disclosure: I didn’t become ill in order to complete this Substack post, but I have to say that the timing was propitious. Among the tumble of thoughts that went through my head, one of the most prominent was the one expressed by Sartre (5). As I saw the distinct possibility of life’s end sloshing toward me through choppy seas ahead, I felt myself sinking below the waves. The great field of possibilities for future lives became a narrow grey tunnel. My event horizon became a barely visible pinpoint that threatened to disappear entirely. It struck me more than once that the very worst thing about ending was that the closer one got to the final curtain, the fewer choices remained to be made. In that bleak thought, I found a glimmering of understanding of why complexity, and the feeling of agency that it engenders, is so important to us and how it connects with the vitality I’ve been telling you about for the past few weeks (6).

There’s a set of ideas that have burbled around in my confused mind for some years now that begin with the 1974 Pulitzer Prize winning book by Ernest Becker entitled The Denial of Death and travels through some stimulating experimental psychology that normally falls under the rubric of terror management theory. Becker’s argument was that we humans, to cope with our awareness of mortality, engage in elaborate defence mechanisms. One kind of defence is that of escape. We drink, take drugs, have sex, play Xbox, anything to find relief from the clutches of the reaper who waits for us at the end of the road. But another kind of defence involves what Becker called “immortality projects” in which we try to throw off the yoke of mortality by engaging in activities that throw our existence into a posthumous future. In other words, we make stuff—literature, painting, buildings, in order to rage against death in the “defiant creation of meaning.” More than anything else, Becker argued, these pursuits define us as humans (7). I’ve often turned to Becker’s arguments in my own discussions of the origins of architecture as a way into thinking about the relationship between building and feeling (8).

The extension of Becker’s thinking into more explicitly psychological matters comes from a group of psychologists who have advanced what they have called Terror Management Theory, and which they’ve supported with a large number of provocative experiments. The kernel of their argument is that our awareness of mortality and our consequent terror of death is something that we manage through adjustments in behaviour. One simple/not-so-simple example of this might be the tilt towards conservative politics in the United States following the 9/11 terror attack in New York. As the argument goes, when we are threatened by reminders of our own mortality, we move toward conformity, the safety of the group, and the traditional values offered (perhaps….) by conservative politics. And presto, GWB was re-elected.

Now all of this explanation of the context of the psychology of mortality is a little bit of a tangent to what I want to suggest, nor do I mean to defend terror management theory, which seems to have fallen a little out of favour in some quarters. For Becker, though, our awareness of and consequent shrinking from the idea of death was a kind of a design flaw. Defending against our own mortality gave rise to a great deal of evil and suffering (9).

But as true as that might be, it’s also the case that while we live, we carry within us a small grain of uncertainty. Each of us may die today, tomorrow, next Wednesday or in fifty years. And it’s that grain of uncertainty both for me about my life but also for me about your life that contains the wellspring of agency. At any given moment, I don’t really know exactly what happens next. I don’t know what I will do and I don’t know what you will do. And that’s it. It’s the incalculable complexity, uncertainty, and mystery of the next moment from which my perception of agency, both mine and that of the other, ensues. This uncertainty is the very home of agency. It’s where will lives. For some dour reductionists, the very idea of will is, perhaps, illusory. Though the wheels and cogs may be invisible to us, our fates are determined from the beginning. But even if this is so, I can live with the contradiction that the appearance of uncertainty and the life that it entails is enough to get me across the finish line from one day to the next.

So no wonder that we are preternaturally tuned to detect and love complexity, entropy or whatever you’d like to call it. It seems the very signature of life. And life, as the opposite of death, is where agency lives.

Self-indulgent footnotes

(1). I say “supposed” because in spite of my finely-honed search skills, I cannot find the source of this quote. It does sound as though J-P might have said it but it bothers me that I can’t find a proper source. If you know the source, it won’t be cheeky to mention it in the comments or to get in touch with me in some other way.

(2). Gitanes or even exotic Sobranies when I could get them.

(3). To quote Holden Caulfield, you can immediately see what a “royal pain in the ass” I was.

(4). And good news – my ultimate fate was forestalled and I expect to be here to torture you for many more years

(5). Along with abject fear about the future welfare of my offspring and my wife, others included that I might never complete the scale model of the HMS Victory that I’d been dreaming about, that I might never grow a perfect tomato, and that I might never know how the HBO series Succession ends.

(6). Sounds weird to say that I was thinking about this when I should have been “putting my affairs in order” as they say, but that’s just me. I was doing both. Even in the face of death, it’s important not to be boring.

(7). This is a paltry account of Becker’s staggering reach as a scholar. As always, don’t believe me. Read the book.

(8). Stopping there on that. You can read my book Places of the Heart for more if you like. I talk a bit more about this there.

(9). War, genocide, nationalism, rejection of the outsider…all of which is unfortunately familiar to everyone, especially right now.

What I’m reading

I just finished Richard Powers’ Pulitzer winning novel The Overstory. I picked this up at the urging of my intrepid literary agent who went so far as to suggest that this book might be considered a “competing title” with something that I’ve been writing. Confused because I’m not writing a novel, I dove in. I learned a great deal about trees from the book and also about people and the connections between the two. I remembered many things about so-called eco-terrorists defending old-growth forests and was stimulated by themes connecting human agency with forests. There’s even a leading role for a metaverse-creator in the novel, which provoked me. It was a good book to distract me from the mountain of more technical stuff that I have to soon go back to reading now that my little existential crisis is fading into the past. It’s also made it impossible for me to see a simple piece of wooden furniture in the same way as before. Grain carries meaning.

What I’m eating

Ok, this is a little bit boring because I haven’t been cooking very much lately, leaving the hard work of meal-making to my beleaguered wife who has had to do, well, everything, for the past little while. But like much of the rest of the planet, I’ve been baking bread. The image below is a reasonably successful boule of no-knead bread. I’ve tried various recipes to make bread. They all work to one degree or another. Most are a bit too chewy but all seem to make phenomenal toast. For Christmas, my niece gave me a beautiful book about bread-making that I haven’t yet worked up the courage to adopt completely. The main recipe calls for a few hacks to my conventional gas oven that might either a) shatter the glass door or b) destroy the electronics of the oven or c) burn down our house. Timing for any of these things is, of course, tricky. In the meantime I’ve occupied myself with the acquisition of gadgets for bread-making. Soon, though.

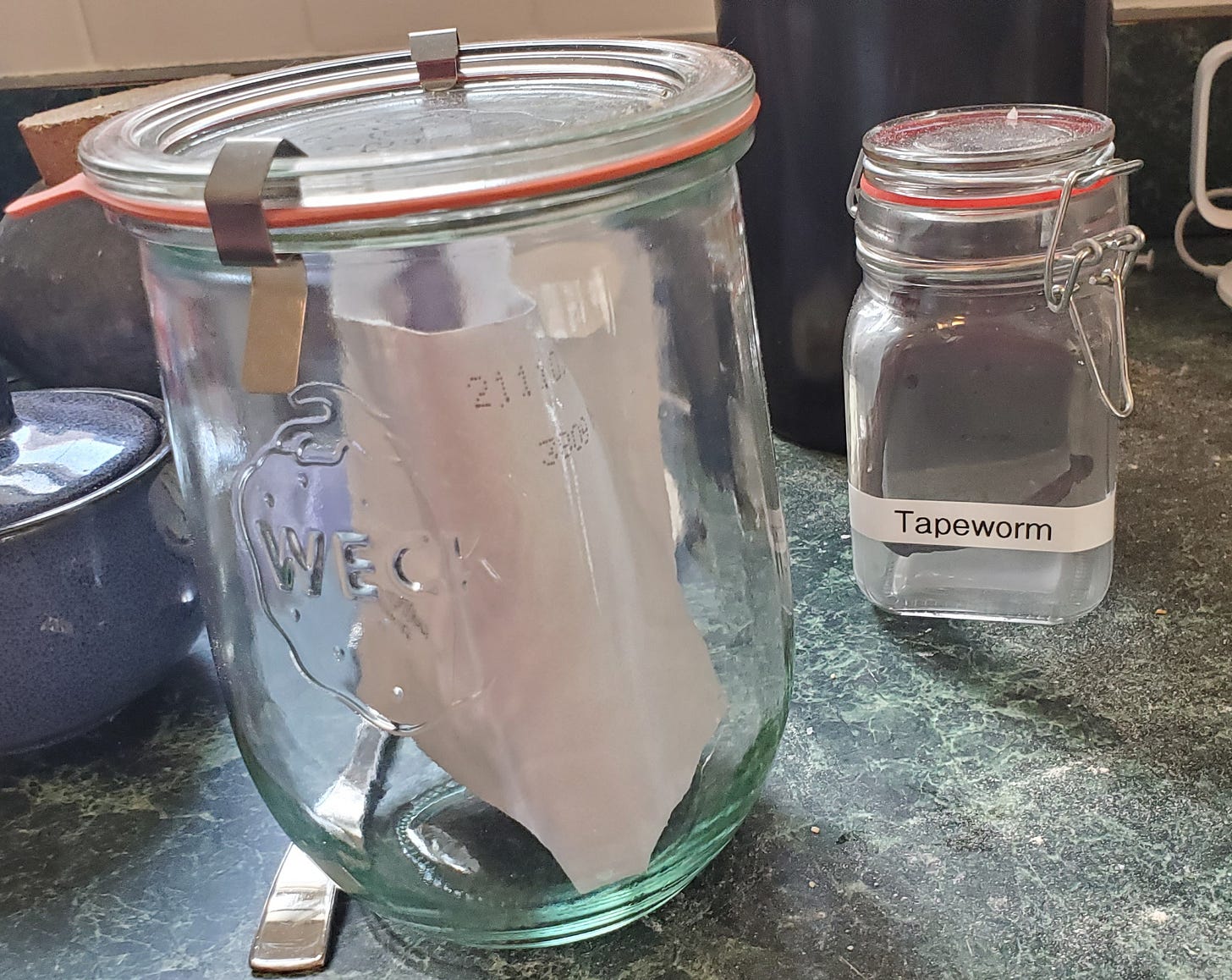

I’ve also been toying with sourdough. I bought an inactivated starter culture, pictured below, which, at least according to the character who sold it to me, had its origins during the Klondike Gold Rush when bread makers slept with their cultures to keep them warm. Soon I’ll try to activate it (the bread, that is, and not the sleeping arrangement).

I couldn’t resist including another jar in the image. You’ll be relieved to know that I don’t actually keep a tapeworm on my kitchen counter. That’s a shrivelled vanilla bean that was a part of a birthday gift from an equally delightful niece. Caption provided by my witty and helpful wife. Sounds odd but the vessel was originally filled with a nice bourbon. If you like bourbon, I implore you to try this. Infuse with a vanilla bean for a few days. You’ll end up drinking more bourbon than is good for you. You can save your liver by using a smallish jar. But please don’t use a tapeworm even if you can find one.