At a recent work meeting, the subject of synchrony came up. The context was this paper, which purports to show that physiological synchrony in measures of heart and skin variables predicted attraction between two people in a speed-dating scenario. I can’t remember the relevance of this finding to our conversation, but I think that somehow in the airy climate of free exchange the thought was that one might be able to use a synchrony measure to learn interesting things about social interactions. In the current climate where we are struggling to find ways to overcome the crisis of urban loneliness by means of design mods, this was a tantalizing idea.

After our brief meeting, and as seems to happen to me nowadays, I ended up disappearing down several different rabbit holes. I’m now trying to figure out whether all those holes belonged to the same rabbit. I’ve said here before that though I’m not a woo-woo kind of person, it strikes me sometimes that the seeds of everything that I’m currently interested in can be found in some weird project or activity of one of my early, former selves.

Early in my career, I was interested in one of the most vexing problems faced by any animal, that of not being eaten by something else. It was less a gory interest in predator-prey interactions and more that it seemed to me that this was one of the most urgent problems that animals had. There was little room for learning, no tolerance for trial-and-error, and a great demand for precision. Whatever an animal could do in the way of understanding and commanding space, we’d likely see its best efforts here. I spent many happy years thinking about how all of this worked for one little animal, the Mongolian gerbil, and I published many papers in the arcane corners of the scientific literature.

One quirk of behaviour of these animals, which you’ll know if you’ve ever had one as a pet, is that their movement style is a little bit herky-jerky. The scientific term for herky-jerkiness is saltatory locomotion from the Latin term “saltare” for jumping. In this case, it means that gerbils move by running forward a step, pausing briefly, running another step, all of this often interspersed with upward rearing movements, presumably to have a look around at what’s going on. If you’ve ever watched a chipmunk, you’ll notice the same pattern of movement. Watching this saltatory movement, it occurred to me that a savvy predator might be able to catch a gerbil by attending to its movements and timing an attack to avoid those moments of upward rearing and presumed vigilance. In fact, as my work often involved capturing gerbils (though happily not to eat them), I felt that I also took advantage of the herks and jerks to make my job easier. So, what’s a fledgling fruit-and-nut scientist to do but to gather up thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment – cameras and computers mostly – and see what could be seen. It did seem as though the pattern of movement was regular and predictable enough that a watchful predator would have an easy time of things. But then the gerbil being the kind of critter that lives in groups, I wondered what would happen if I tried to measure movements in more than one gerbil at a time. If two gerbils, for example, are unleashed in a sketchy neighbourhood, they might be clever enough to de-synchronize their movements so that they shared each other’s short bouts of vigilance (imagine that the gerbils organize so that one or the other’s head is up and scanning most of the time). There’s a fabulous literature documenting similar group effects in birds, where the larger a group is, the less time everyone must spend scanning and the more time they can spend eating. Indeed, this kind of shared responsibility has been argued to be one of the reasons that any animal endures the complexities of life in a group—shared responsibility against threat (1). A fascinating perspective on these kinds of behaviours is that they point towards theory-of-mind research that looks at how we implicitly (or in the human case explicitly) model the minds of other beings to glean some advantage. If I assume that when you pop your head up for a look you are doing the same thing that I do when I pop up my head then I can leverage that understanding to make my own life a bit easier. The behaviours themselves don’t by any means “prove” any fancy mind models on the part of pecking birds, but they may suggest things about the roots of the fancier stuff.

Sanjeeban Nanda, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The end of my own laboratory research in synchrony was unremarkable. As a young assistant professor swamped with duties and accustomed to seeing the sun rise in my office as I scrambled to get lectures ready, I abandoned this line of research as one of too many side-projects that I didn’t have time for. So, I can only tell you that I had good evidence that groups of gerbils know about one another’s position and which way they are going, but I’m not sure they are clever enough to share vigilance as birds seem to do. Maybe.

This hasn’t been my only history with synchrony though. In fact, as the father of a new little daughter, I’ve been remembering research that I did many years ago on the behavioural synchronies that exist between parent and child (2). One of the many miracles that happens while raising a baby is that moment when you are sure that your baby has noticed what you are doing, and she tries to mimic it. In fact, the endless handouts and checklists that come from doctors’ offices specify some of these things – the age at which you might expect a baby to smile back at you, for instance. Noticing the first few instances of this, when you are sure that you have connected with this perfect, squirming little being that somehow you were allowed to take home from the hospital, is electric. It’s like first contact with an alien being, but an alien with a face designed to make you fall in love, rather than, say, frighten you with its green skin and eyes on stalks. Our little being, now at the ripe old age of 3 months, is well beyond these initial fleeting moments of recognition and we are into full-bore communication. We have hooting contests. She demands foot kisses. We even think that she is archly raising one eyebrow at us when she notices something ridiculous or funny in our behaviour (very frequent at our house).

The first such interactions, though—those sweet calls and responses—come from the baby’s own mind and her own body. When she does some mysterious, nameless thing with her brain that causes her arm to flail upwards and then she sees that arm move, a cerebral penny drops: “Hey I did that! That flailing arm belongs to me!” This is the very birth of the feeling of agency—first I learn that I am the agent of my own body but then, even more miraculously, I realize I am agentic to other beings as well. When my dad’s big hairy face hovers over me, I know that if I hoot, he will hoot back (3). Seeing all of this unfold in real time is an incredible privilege and blessing. It’s both achingly slow as we anticipate whatever is going to happen next and blindingly fast as she sometimes wakes up with an entirely new tool in her little kit, as if a fairy had sneaked into the nursery overnight and showered magic dust on her (4).

As long as everything is ok, agency and the feeling of agency will continue to develop in children and, just as with adults, the feeling that you have the power to affect your surroundings is an essential part of wellness and, as we know from a history of truly nasty experiments in psychology, even animals give up all hope when put into a situation where they can’t change their own awful plight. It goes by the bland-sounding term “learned helplessness,” and it isn’t just animals in labs that suffer from this state but humans as well. Think of incarcerated humans or victims of abuse. Learned helplessness is sadly common.

One of the first experiments I did as a student of psychology was for an undergraduate course in human development. I was cocky enough that I decided that rather than write a perfunctory essay on the famous child psychologist Piaget, I’d go out into the field and do an experiment. I shunned Piaget in favour of the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, mostly because I thought that was a bit more exotic choice that would go along with my affectations of being a tortured and brilliant outsider and it might make me more interesting to the women in my class (6). That part didn’t work out very well (7).

Without being too boringly discursive, I’ll just say that Vygotsky argued that children need interaction—the pushing and pulling with the environment—to develop properly. In other words, they need to feel agency. For my experiment, I went to a well-known creative playground in Toronto at the time at a wonderful lakefront development called Ontario Place. I imagined that I would see all kinds of evidence of developing agency as I sat on an adjacent hillside watching children, taking notes, and eating fries. The surprising thing, and the basis of my report to the class, was that in the midst of a paradise of creative and interactive tools for play, most children spent all their time ringing a large bell while looking around to see who was listening. This struck me as such a simple and obvious example of developing agency that I based my entire report on it and received an A+ and some fawning attention from the professor.

I don’t think adulthood is much different when it comes to our cravings for agency. We want to feel that our individual actions matter and that our personhood is important. We want to be listened to. We want others to know we are here. We want to feel that we have control over where we go and what we do. We may not feel the same frisson of excitement as that between parent and child, but unless we have at least a modicum of those kinds of feelings of agency, I think it’s very hard to be happy. These general truths about what I think it takes to flourish as a human being also have implications for how to build psychologically sustainable architecture and cities. In fact, I’ve come to think that the most important ingredient in the design of a city is that it affords genuine agency to its residents. My earliest dalliance with agency and architecture came from a periodic connection with architect and artist Philip Beesley, who designs interactive, “living” systems that point to the possibility of empathic relationships between built structures and human beings. His creations, massive networks of sensors and beautifully designed fern-like materials that look very much like alien forests, are shimmering, vital things that attract long lineups for a glimpse of them and then often freeze viewers into a state of awe and then delight. Those who know me well know that I’m, at best, middling about the possibilities for this kind of interactivity in bread-and-butter architecture (8) but, as an explicit example of what’s possible and as a stimulus for thought, Beesley’s creations are disturbing and disorienting in the best possible way.

These days, I’m more interested in the more subtle ways that interactivity and agency might work in relationships between humans and buildings. As one example, I wrote here recently about the give-and-take between human and environment that has to do with scale. In comparing a massive construction in Paris (La Défense) and a beautiful little square in Venice (Campos Santa Margherita), and thinking about how one might make you feel held, nurtured, and perhaps even loved while the other might feel cold and forbidding, I suggested that one reason that a massively scaled environment might make you feel irrelevant is that there would be no experience of parallax in such a setting. When things are big and far away, you don’t notice how your own movements cause changes in your perspective. When things are close and small, every movement you make is reflected in a changed perspective. Perhaps a little bit like the call-and-response between a child and a parent, a setting like Campos Santa Margherita seems as though it sees and acknowledges me. I feel my own agency in a setting like this. I don’t think it’s a long stretch to think of this kind of interaction between environment and person to be an instance of synchrony. What matters is that I notice the impact of what I do. I can read out my own intentions by experiencing my surroundings.

Other than scale, an open and interesting question is whether there are other ways that synchrony manifests in relationships between a design and a visitor to that design. In part it must have to do with our desire to be seen and understood, if not always by the structures, then by the creators of the structures. An example that comes to mind is of a long walk that my wife and I took some years ago through the streets of the city of Toronto. It was a sweltering summer day, and our route took us down a long, somewhat uninteresting thoroughfare with a notable absence of interesting sites or even good landscape architecture. But what really got to us was the fact that, for a long stretch of our walk, there was nowhere to sit. When we finally found a bench for a short rest and recon, it was crammed into the side of a building and facing the wrong direction such that any occupants of the bench had nothing to see except for a concrete wall in front of them. Whatever irritation we might have felt along with our exhaustion and dehydration, we also felt a distinct lack of affection—both ours for the setting and the setting’s for us. That bench, and whomever put it there, didn’t care about us. We felt unloved. The reason that I see this as an example of synchrony or, more accurately in this case, desynchrony, is that with a good design the benches might have been around when we wanted them. You can imagine there being a rhythm to successful designs. It isn’t just what’s there but where it is, and that where must be conditioned by the rhythms of human movement. I’m sure you can think of examples of your own favourite places where there is an elegant match between your wants and needs and the affordances of the setting. You like a particular little park, let’s say, because when you feel like sitting down there’s a spot right before you for doing so. It’s almost as if loving but invisible hands were expecting you before you arrived and knew what you would need. To me, that’s synchrony.

To take one final step, let’s think about how the design of a space might have an impact on synchronous relationships between individuals. Going back to the birds using one another’s views of the world to help protect themselves against predators, it’s also likely that the environment conditions the likelihood that something like that might work. If the birds can’t find a spot where they can share separate vantage points on a part of space, shared vigilance is not going to work very well. In a parallel way, the design and location of places of rest and repose in a setting is going to influence the likelihood that people with similar needs and aspirations (9) will meet and talk to one another. In ways perhaps both bluntly obvious and much more subtle, synchrony could be encouraged by good design.

I’ll just close by mentioning one other connection between these meanderings and other of my passions. In the kind of context that I’m using it, the very word synchrony implies intersections in both space and time. Regular readers will already know I have a small obsession with time in the sense that most of the science in my field focuses far too much on space and not enough on time. Many of us do experiments where we ask participants to stare at pictures of things or, only slightly better, we take them out into the world to look at stuff in field studies. But that’s almost like trying to understand our engagement with the built world as if it comes from perusal of a series of static images like Cezanne’s still life paintings. It’s only when we consider unfolding experience over time, and the capacity that this unfolding offers for human experience that things really start to soar. The real treasure, as we first learn as infants and find reinforced over a lifetime of experiences comes in encounters with synchrony, agency, and, ultimately, the feeling that someone or something knows that we exist, knows how we might feel, and knows how to care for us.

Meandering notes

1. Incidentally, this is one of the things that we tend to discuss less in the context of loneliness. Why do we humans need to be social at all? Yes, there are clear material advantages to life in a group, but why is it that when we lack connection with a group we suffer so much that our bodies recoil and our lifespan shortens?

2. And by “research” here I mean mostly reading articles and noticing in a kind of Piagetian way the stuff that happens with my own children as they grow.

3. Or sometimes, for reasons that nobody understands, including himself, he will utter the refrain “Oompah Loompah Poopah Scoopah” which will cause both of us to dissolve in leg-wiggling mirth for a few seconds.

4. And I call myself a scientist, though perhaps just a fruit-and-nut one.

5. psychologists aptly named this state “learned helplessness.’ It happens a lot with humans as well but I’m not going to write about it. It’s too sad a thing for a nice late-summer day).

6. Full disclosure is that I was a typically formless and insecure young man living in his parents’ basement in the suburbs of Toronto.

7. Though my wife has just suggested that another factor in my ill luck might have been that I didn’t brush my teeth often enough. Possible.

8. Like most people, I think, I don’t want an environment that predicts my next move and throws up supportive bumpers around me. I like a bit of friction.

What I’m reading

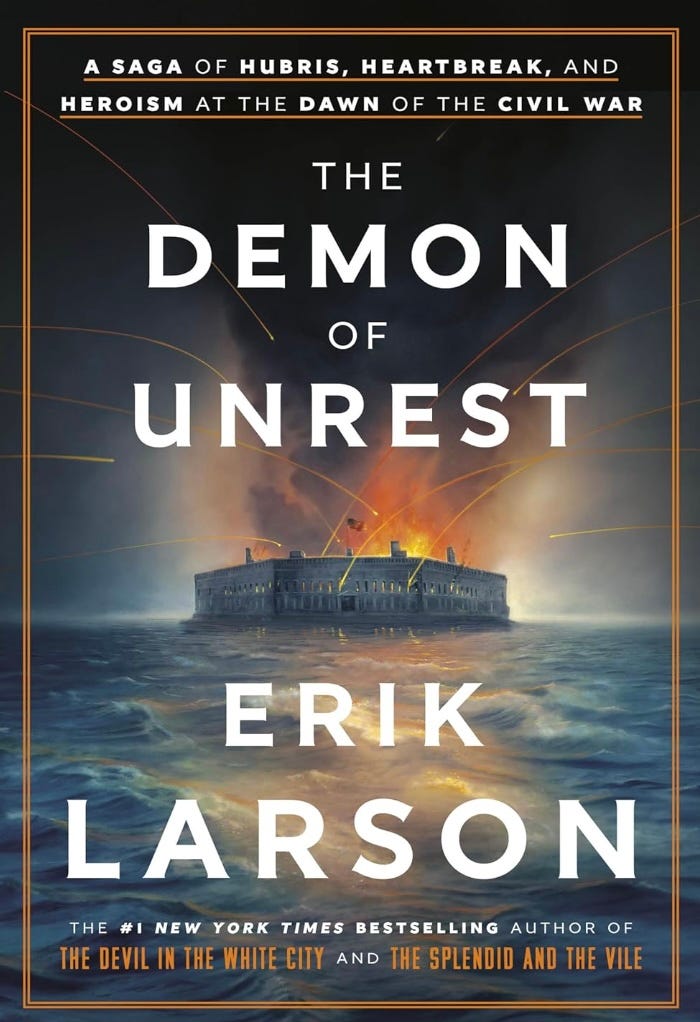

I have to tell you — as a new/old parent (baby in the house after a baby gap of about 20 years), I’m not reading as much. We’ve discovered that our little girl has incredible spidey sense for when we are about to sit down for dinner (smell of food?) and when papa sits down to write (the gentle ticky tack of the keyboard). The book that I’m carrying around the house at the moment is Erik Larson’s Demon of Unrest. Truly one of my favourite authors and a book to be savoured and, at this moment in history, somewhat terrified by.

What I’m eating

You’d think that given our life stage the menu at Chez Ellard might be whatever can be grabbed with one hand while dandling a baby, but honestly we are both home a fair bit and I sometimes have time to cook. One of our favourite social events these days is the periodic visit from my Sister Jenn who lives quite a distance from us but somehow manages to make the trek here to visit baby and parents. She’s a vegetarian, so Lady Kristine’s gambit is to pitch some ambitious recipe that I’ve never made before and to let me go to it. For our most recent visit, I made a Beet Wellington with a balsamic glaze, pictured below. I’m not a food photographer so the pic doesn’t do justice but all agreed that the half-day of my labour was well-worth the effort. As usual, I complained all day long that I would never make this again and then, before knife and fork were even back on the plate, I was planning an encore performance. Next dinner party: vegan toad-in-the-hole with miso gravy. Tummy already growling.

Great article, I enjoy your writing style and the topic was right up my alley :)